Columbia Insights for Executives

William G. Pietersen

Professor,The Practice of Management

Columbia Business School

©2005

Companies create their futures through the strategies they pursue. These strategies may be explicit or implicit; they may be developed in a thoughtful, systematic way, or allowed to emerge haphazardly in a series of random, ad hoc decisions made in response to daily pressures.

But in one way or another, the strategy a company follows – that is, the choices it makes—determines its likely success. And in today’s fast-changing environment, the ability to generate breakthrough strategy and to do so not once but repeatedly, has become more important than ever.

Most executives would readily acknowledge these truths about the importance of strategy. It’s curious therefore, that few companies have devoted significant time or energy to considering the nature of strategy or to examining their own method for developing strategy. Instead, many of them simply plunge directly into strategy formulation. It’s as if the manager of an auto plant were to dump a load of parts onto the factory floor and tell the workers, “Here, make some cars,” without defining a manufacturing process with the end-product in mind.

In this paper, we’ll take a step back and consider the basic questions that companies need to confront:

- What is strategy?

- What is the role of strategy in an organization?

- What is the best method for creating strategy?

What is strategy?

Perhaps the best way to understand strategy is to consider why it is necessary. Strategy exists because of the stark reality of limited resources, which forces organizations to make choices about how best to use those resources in the pursuit of competitive advantage. Strategy is simply the sum of a company’s choices about where it will compete, how it will create superior value for its customers, and how it will generate superior profits for itself.

Competition expresses itself through the interaction of choices in the marketplace. The best strategic choices, well executed, will win the game.

What is the role of strategy in an organization?

In a world of limited resources, a company that tries to compete in every market with no specific focus or direction will soon squander its resources and fall behind its competitors. Strategy’s central role is to provide the focus and direction essential to successful competition.

Just as important, strategy also provides a platform for an organization’s leaders to engage the hearts and minds of employees in pursuit of a winning way. Thus, strategy and leadership are essential parts of each other. No leader can lead successfully without a clear and compelling strategy; and no strategy, however brilliant, can produce results without effective leadership. The unifying concept that expresses this essential synergy is “strategic leadership.”

On the other hand, although strategy and planning are often combined under the rubric of “strategic planning,” they are totally different things. Strategy is mainly about ideas, while planning is mainly about numbers, budgets, and logistics. Strategy defines where to lay the railroad tracks, while planning is about making the trains run on time. Both are essential, but combining them in one process is a toxic mixture. The golden rule is: strategy first, and planning afterwards, with separate and robust processes for each.

What is the best method for creating strategy?

Now that we have clarified the nature of strategy and its role in the organization, the crucial question becomes: How can we create brilliant strategies for our company? Which method should we choose?

This is no easy decision. There are a bewildering number of gurus, consultants, and writers, each with a strongly held view on how strategy should be created. Which one is right?

The truth is that there is no silver bullet. Each approach to strategy creation has its advantages and disadvantages. Corporate leaders must decide for themselves which method is best for their organization. But there are sound principles we can use to make that choice. Here are the four criteria I suggest for choosing a strategy approach:

- Is it compelling in terms of cold business logic?

- Is it simple enough for everyone to understand and embrace?

- Is it designed to produce the right outputs?

- Does it offer practical tools to get the job done?

With these criteria in mind, let’s consider the different methods that are available to us. Broadly speaking, there are four main schools of thought regarding strategy creation:

- The Resources School

- The Innovation School

- The Positioning School

- The Learning Organization School

Each school is based on its own set of underlying assumptions about what matters most, which in turn drives a particular set of beliefs about strategy development. The four schools share certain assumptions and beliefs; many of the differences among them are matters of emphasis. But this is not a trivia distinction; many of our biggest decisions are determining what’s important.

Before reviewing each of these approaches, let me declare that I am no agnostic; I have a point of view about which method of strategy development works best. My aim is to describe the alternatives as objectively as possible, so that readers can form their own judgments. And then, in conclusion, I will offer my own point of view.

1. The Resources School

The underlying argument of this approach, perhaps best formulated by C. K. Prahalad of the University of Michigan School of Business in his book Competing For the Future (co-authored with Gary Hamel), is that each company has a singular set of resources (often called core competencies) that differentiates it from its competitors, just as a champion tennis player has a set of killer strokes in his arsenal. In this view, the key to success is for a company to discover these core competencies (by answering the question “what are we best at?”) and then leverage them across the organization to seize and maintain competitive advantage. If a company keeps improving its unique skills and embeds them deeply in the organization, competitors will find them increasingly hard to copy.

Here are examples of well-known companies and the core competencies that have helped make them successful:

Company ------------Core Competency

Samsung---------------Miniaturization

Toyota-----------------Product quality

Avon-------------------Direct selling

Wal-Mart--------------Supply chain management

Strengths. The Resources school recognizes the power of aligning the entire business system (including the corporate culture) behind a winning formula. It works wonderfully well so long as there is a good fit between the core competencies and the requirements of the external environment. If your core competency produces a result highly valued by your target customers, a strategy based on leveraging that competency is likely to succeed.

Limitations. The Resources approach to strategy tends to encourage inside-out thinking (“What are we best at?”) rather than outside-in thinking (“What do our customers need?” “What are our competitors offering?”). The danger is that such thinking may lead to a static view of the world in which critical shifts in the environment are ignored, even as they render a company’s strategy obsolete.

2. The Innovation School

This approach, advocated by authors like Tom Peters (Thriving on Chaos) and Gary Hamel in his more recent work (Leading the Revolution), focuses on the dilemma faced by organizations, which tend to lapse into bureaucracy and inertia—what scientists call homeostasis. The result is fixed mental models,an inward focus, institutional resistance to change, and a gradual loss of innovative capacity. All are strategically debilitating.

As Peters and Hamel point out, most innovations come from newcomers, not established players. For example:

Established-----------------------Firms Strategic Innovators

Xerox------------------------------Canon

Compaq----------------------------Dell

Sears-------------------------------Wal-Mart

Traditional watch companies------- Swatch Watch

In each case, the newcomers drove the established firms into extreme financial distress or even bankruptcy. Such reversals are becoming increasingly common: The average tenure of companies on the S&P 500 has dropped from 65 years in 1930 to just ten years today. Of course, there are exceptions;Procter & Gamble, GE and Disney, for instance, have successfully navigated change over an extended period. But the overall statistics represent a call to action for established companies: Innovate or die.

Strengths. There’s no doubt that innovative capability is a crucial key to long-term survival. A strategy approach that emphasizes innovation will instill the organization with a sense of urgency and an openness to change, both positive traits.

Limitations. On the other hand, the single-minded focus on innovation alone—the relentless pur-suit of the new—may divert attention from winning the existing game. As Mike Tushman of the Harvard Business School puts it, companies must be “ambidextrous,” simultaneously focusing both on innovation and on operational excellence, involving continuous improvement of current processes.

3. The Positioning School

The leading proponent of this approach is Michael Porter, a professor at Harvard Business School, and author of the landmark book, Competitive Strategy. Porter argues that earning superior return on investments(which he considers the chief goal of any company) requires a sustainable competitive advantage—a way of providing value to customers unmatched by competitors.

To capture sustainable competitive advantage, the argument goes, a company needs to establish a favorable positioning within its industry. Here are some examples of companies that have established different but profitable positions in the same industry:

Gillette: High quality re-usable razors and blade

Bic: Cheap disposable razors

Southwest Airlines: Low cost, no frills, point-to-point flights for budget conscious travelers

Singapore Airlines: A superior air travel experience with the finest food, comfort and service available

Porter advocates using the so-called Five Forces Model as a method of industry analysis to help find profitable positioning opportunities. This involves assessing:

Strengths. The strengths of this approach include its focus on capturing competitive advantage and its analytical rigor, drawing on Porter’s background as an industrial economist.

Limitations. Its shortcomings are that it is a somewhat static model, focusing on a snapshot of the industry rather than a dynamic analysis that reveals underlying trends, changes, and patterns. Furthermore, it focuses mainly on industry attractiveness rather than in-depth analysis of customer needs.

4. The Learning Organization School

Champions of this approach include scholars such as Peter Senge (The Fifth Discipline), David Garvin (Learning in Action), and Arie de Geus (The Living Company). Recognizing the failure of much traditional strategic planning, these theorists have been exploring ways to forge a more vital connection between corporate thinking and corporate action. The logic they put forward is essentially Darwinian: Long-term survival is based on an organization’s ability to adapt continuously to a changing environment, and successful adaptation in turn is dependent on effective learning.

This vital link between learning and adaptation has given rise to a body of thinking on how to create a learning organization with an enhanced ability to generate, capture, and share knowledge. In essence,the argument of this school is that organizations must learn their way to success, as crystallized by Arie de Geus in his now-famous statement that “in future, an organization’s ability to learn faster than its competitors may be its only sustainable competitive advantage.”

Examples of companies that have successfully pursued this philosophy are:

Shell Company: Perfected scenario planning as a way of dealing with uncertainty

Buckman Laboratories: Created advanced knowledge-sharing systems to disseminate best practices throughout the company

Cisco Systems: Established a deliberate process for learning from customers, engineers and suppliers to guide its product development programs

Strengths. The identification of adaptiveness as the necessary condition for long-term survival and the linkage between adaptation and the ability of an organization to learn effectively are both persuasive.

Limitations. This approach often positions learning in an open-ended, generalized way, almost as an end in itself, as if learning by itself will result in adaptiveness. This leaves out the essential step that unlocks learning’s value: the hard work of turning learning into breakthrough strategy.

Which approach is best?

As promised, I now offer my own point of view.Each of these approaches has advantages to offer,but none will work long term unless organizations have an effective process to modify their strategies in response to the changing environment. Getting stuck in one place, physically and psychologically, is the greatest danger. Thus, the Learning Organization approach offers the most compelling theory of success.As the learning theorists suggest, adaptiveness is the necessary and sufficient condition for long-term success, and this is driven by the right kind of learning.

However, we need to take this thinking a step further. It is not learning for its own sake, but learning strategically that is the source of successful adaptation.

Here, then, are my key conclusions:

1) Sustainable competitive advantage does not take the form of a particular product, service, or strategy. Rather, it is the organizational capability to be adaptive.

2) It follows then that the central role of strategy must be to help executives create and lead adaptive enterprises. We need to reinvent strategy to serve this purpose.

3) Work gets done in organizations through business processes. Thus, the missing piece in the Learning Organization approach is a practical process to deliver the right strategic outputs.

Strategic Learning

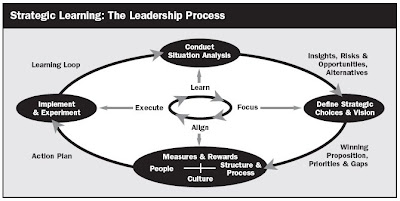

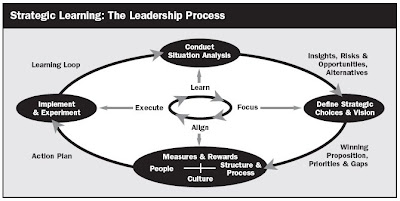

A leadership process I call Strategic Learning aims to offer such a practical, systematic method. It postulates that an adaptive enterprise is one that continually scans and interprets its changing environment and its own realities. Acting on those insights, the organization defines its strategic choices and modifies those choices as circumstances change.

The Strategic Learning process is based on what I call the “killer competencies” of adaptive organizations. These are:

1) Insight: Powerful tools to generate a superior understanding of the changing environment and the firm’s own realities

2) Focus: A robust process to translate these insights into the best choices on where to compete and how to win

3) Alignment: Effective practices to align and energize the entire organization behind the chosen strategy

4) Execution: Rigorous disciplines for executing better and faster than competitors

5) Renewal: A dynamic process for doing these things repeatedly, thus creating a cycle of ongoing renewal

The first four steps of the Strategic Learning process create specific outputs. The fifth ensures that the process is dynamic. These five steps are converted into a practical leadership process through the Strategic Learning Cycle shown below.

It is not enough to do some of these things all the time, or all of them some of the time. The entire cycle needs to be ingrained in the organization through repetition and practice. When this happens, the killer competencies will create an ever-improving organizational capability which will serve as the main source of sustainable competitive advantage.

What’s unique about Strategic Learning? I believe the alternative approaches are not so much wrongas incomplete. Embedding a specific competency is a choice; pursuing a particular innovation is a choice; and adopting a defined position in the market is a choice. In specific circumstances, each may be a valid,even necessary choice. However, defining choices is not the starting point of the strategy-creation process, but rather its outcome. The challenge, after all, is not just making choices, but making the most intelligent choices. The most intelligent choices will be those that are driven by superior insights.

Therefore, the Strategic Learning process insists on two crucial disciplines. First, the strategy process must always start with a Situation Analysis to generate insights about the external environment and the organization’s own realities. The Situation Analysis is the “engine room” of strategy creation, and is designed to reveal patterns and trends, not just snapshots of current truths.

Second, in our dynamic competitive environment, it’s essential that the process be cyclical and self-renewing, not static. As military experts emphasize, strategy must be a process of continuous assessment and reassessment.

Strategic Learning has become the core methodology for teaching strategy in Columbia Business School’s Executive Education programs, and the process is being successfully applied by numerous companies around the world. It’s no silver bullet, but I would argue that it meets the criteria listed early in this paper. Most important, it has been shown to work in practice.

Of course, Strategic Learning has its own limitations. The greatest of these is that it's time consuming. Generating insights is hard, messy, and sometimes frustrating work (although it becomes faster and more efficient as firms master the process through repetition). It demands a real commitment to carve out time on the corporate calendar to get away from the urgent and think about the important.

Furthermore, it requires that strategy and leadership work hand in hand. Top leadership must model the behavior of searching for truth, confronting reality, and making tough choices when necessary. A process alone is not enough. This takes courage.

It all begins with insight

One traditional view of strategy which has informed much thinking on the subject defines strategy as dealing with the relationship among ends, ways, and means. Unfortunately, this formulation suffers from a serious omission—it leaves out insight, which is arguably the most important element of all. It is the quality of the insights that determines the quality of the other three variables. Thus, the correct formulation contains four elements: insights, ends, ways, and means.

In our increasingly complex environment, it is the battle for superior insight where the competition really begins. In today’s business wars, this is increasingly the decisive battleground.

You can learn more about Strategic Learning in Willie Pietersen’s book, Reinventing Strategy (John Wiley & Sons, 2002), or by consulting his website www.williepietersen.com.

Limitations. The Resources approach to strategy tends to encourage inside-out thinking (“What are we best at?”) rather than outside-in thinking (“What do our customers need?” “What are our competitors offering?”). The danger is that such thinking may lead to a static view of the world in which critical shifts in the environment are ignored, even as they render a company’s strategy obsolete.

2. The Innovation School

This approach, advocated by authors like Tom Peters (Thriving on Chaos) and Gary Hamel in his more recent work (Leading the Revolution), focuses on the dilemma faced by organizations, which tend to lapse into bureaucracy and inertia—what scientists call homeostasis. The result is fixed mental models,an inward focus, institutional resistance to change, and a gradual loss of innovative capacity. All are strategically debilitating.

As Peters and Hamel point out, most innovations come from newcomers, not established players. For example:

Established-----------------------Firms Strategic Innovators

Xerox------------------------------Canon

Compaq----------------------------Dell

Sears-------------------------------Wal-Mart

Traditional watch companies------- Swatch Watch

In each case, the newcomers drove the established firms into extreme financial distress or even bankruptcy. Such reversals are becoming increasingly common: The average tenure of companies on the S&P 500 has dropped from 65 years in 1930 to just ten years today. Of course, there are exceptions;Procter & Gamble, GE and Disney, for instance, have successfully navigated change over an extended period. But the overall statistics represent a call to action for established companies: Innovate or die.

Strengths. There’s no doubt that innovative capability is a crucial key to long-term survival. A strategy approach that emphasizes innovation will instill the organization with a sense of urgency and an openness to change, both positive traits.

Limitations. On the other hand, the single-minded focus on innovation alone—the relentless pur-suit of the new—may divert attention from winning the existing game. As Mike Tushman of the Harvard Business School puts it, companies must be “ambidextrous,” simultaneously focusing both on innovation and on operational excellence, involving continuous improvement of current processes.

3. The Positioning School

The leading proponent of this approach is Michael Porter, a professor at Harvard Business School, and author of the landmark book, Competitive Strategy. Porter argues that earning superior return on investments(which he considers the chief goal of any company) requires a sustainable competitive advantage—a way of providing value to customers unmatched by competitors.

To capture sustainable competitive advantage, the argument goes, a company needs to establish a favorable positioning within its industry. Here are some examples of companies that have established different but profitable positions in the same industry:

Gillette: High quality re-usable razors and blade

Bic: Cheap disposable razors

Southwest Airlines: Low cost, no frills, point-to-point flights for budget conscious travelers

Singapore Airlines: A superior air travel experience with the finest food, comfort and service available

Porter advocates using the so-called Five Forces Model as a method of industry analysis to help find profitable positioning opportunities. This involves assessing:

- The bargaining power of buyers

- The bargaining power of suppliers

- The level of rivalry amongst existing competitors

- The threat of substitutes

- The barriers to entry

Strengths. The strengths of this approach include its focus on capturing competitive advantage and its analytical rigor, drawing on Porter’s background as an industrial economist.

Limitations. Its shortcomings are that it is a somewhat static model, focusing on a snapshot of the industry rather than a dynamic analysis that reveals underlying trends, changes, and patterns. Furthermore, it focuses mainly on industry attractiveness rather than in-depth analysis of customer needs.

4. The Learning Organization School

Champions of this approach include scholars such as Peter Senge (The Fifth Discipline), David Garvin (Learning in Action), and Arie de Geus (The Living Company). Recognizing the failure of much traditional strategic planning, these theorists have been exploring ways to forge a more vital connection between corporate thinking and corporate action. The logic they put forward is essentially Darwinian: Long-term survival is based on an organization’s ability to adapt continuously to a changing environment, and successful adaptation in turn is dependent on effective learning.

This vital link between learning and adaptation has given rise to a body of thinking on how to create a learning organization with an enhanced ability to generate, capture, and share knowledge. In essence,the argument of this school is that organizations must learn their way to success, as crystallized by Arie de Geus in his now-famous statement that “in future, an organization’s ability to learn faster than its competitors may be its only sustainable competitive advantage.”

Examples of companies that have successfully pursued this philosophy are:

Shell Company: Perfected scenario planning as a way of dealing with uncertainty

Buckman Laboratories: Created advanced knowledge-sharing systems to disseminate best practices throughout the company

Cisco Systems: Established a deliberate process for learning from customers, engineers and suppliers to guide its product development programs

Strengths. The identification of adaptiveness as the necessary condition for long-term survival and the linkage between adaptation and the ability of an organization to learn effectively are both persuasive.

Limitations. This approach often positions learning in an open-ended, generalized way, almost as an end in itself, as if learning by itself will result in adaptiveness. This leaves out the essential step that unlocks learning’s value: the hard work of turning learning into breakthrough strategy.

Which approach is best?

As promised, I now offer my own point of view.Each of these approaches has advantages to offer,but none will work long term unless organizations have an effective process to modify their strategies in response to the changing environment. Getting stuck in one place, physically and psychologically, is the greatest danger. Thus, the Learning Organization approach offers the most compelling theory of success.As the learning theorists suggest, adaptiveness is the necessary and sufficient condition for long-term success, and this is driven by the right kind of learning.

However, we need to take this thinking a step further. It is not learning for its own sake, but learning strategically that is the source of successful adaptation.

Here, then, are my key conclusions:

1) Sustainable competitive advantage does not take the form of a particular product, service, or strategy. Rather, it is the organizational capability to be adaptive.

2) It follows then that the central role of strategy must be to help executives create and lead adaptive enterprises. We need to reinvent strategy to serve this purpose.

3) Work gets done in organizations through business processes. Thus, the missing piece in the Learning Organization approach is a practical process to deliver the right strategic outputs.

Strategic Learning

A leadership process I call Strategic Learning aims to offer such a practical, systematic method. It postulates that an adaptive enterprise is one that continually scans and interprets its changing environment and its own realities. Acting on those insights, the organization defines its strategic choices and modifies those choices as circumstances change.

The Strategic Learning process is based on what I call the “killer competencies” of adaptive organizations. These are:

1) Insight: Powerful tools to generate a superior understanding of the changing environment and the firm’s own realities

2) Focus: A robust process to translate these insights into the best choices on where to compete and how to win

3) Alignment: Effective practices to align and energize the entire organization behind the chosen strategy

4) Execution: Rigorous disciplines for executing better and faster than competitors

5) Renewal: A dynamic process for doing these things repeatedly, thus creating a cycle of ongoing renewal

The first four steps of the Strategic Learning process create specific outputs. The fifth ensures that the process is dynamic. These five steps are converted into a practical leadership process through the Strategic Learning Cycle shown below.

It is not enough to do some of these things all the time, or all of them some of the time. The entire cycle needs to be ingrained in the organization through repetition and practice. When this happens, the killer competencies will create an ever-improving organizational capability which will serve as the main source of sustainable competitive advantage.

What’s unique about Strategic Learning? I believe the alternative approaches are not so much wrongas incomplete. Embedding a specific competency is a choice; pursuing a particular innovation is a choice; and adopting a defined position in the market is a choice. In specific circumstances, each may be a valid,even necessary choice. However, defining choices is not the starting point of the strategy-creation process, but rather its outcome. The challenge, after all, is not just making choices, but making the most intelligent choices. The most intelligent choices will be those that are driven by superior insights.

Therefore, the Strategic Learning process insists on two crucial disciplines. First, the strategy process must always start with a Situation Analysis to generate insights about the external environment and the organization’s own realities. The Situation Analysis is the “engine room” of strategy creation, and is designed to reveal patterns and trends, not just snapshots of current truths.

Second, in our dynamic competitive environment, it’s essential that the process be cyclical and self-renewing, not static. As military experts emphasize, strategy must be a process of continuous assessment and reassessment.

Strategic Learning has become the core methodology for teaching strategy in Columbia Business School’s Executive Education programs, and the process is being successfully applied by numerous companies around the world. It’s no silver bullet, but I would argue that it meets the criteria listed early in this paper. Most important, it has been shown to work in practice.

Of course, Strategic Learning has its own limitations. The greatest of these is that it's time consuming. Generating insights is hard, messy, and sometimes frustrating work (although it becomes faster and more efficient as firms master the process through repetition). It demands a real commitment to carve out time on the corporate calendar to get away from the urgent and think about the important.

Furthermore, it requires that strategy and leadership work hand in hand. Top leadership must model the behavior of searching for truth, confronting reality, and making tough choices when necessary. A process alone is not enough. This takes courage.

It all begins with insight

One traditional view of strategy which has informed much thinking on the subject defines strategy as dealing with the relationship among ends, ways, and means. Unfortunately, this formulation suffers from a serious omission—it leaves out insight, which is arguably the most important element of all. It is the quality of the insights that determines the quality of the other three variables. Thus, the correct formulation contains four elements: insights, ends, ways, and means.

In our increasingly complex environment, it is the battle for superior insight where the competition really begins. In today’s business wars, this is increasingly the decisive battleground.

You can learn more about Strategic Learning in Willie Pietersen’s book, Reinventing Strategy (John Wiley & Sons, 2002), or by consulting his website www.williepietersen.com.

0 comments:

Post a Comment